Exhibition at Cankarjev Dom, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2013

Words of Zdenko Huzjan, Slovenian painter, graphic artist, sculptor and poet, born on September 13, 1948. He is a professor of drawing and painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Ljubljana and the Faculty of Education, University of Ljubljana. It has a long career as an internationally renowned Slovenian artist.

Words of Zdenko Huzjan, Slovenian painter, graphic artist, sculptor and poet, born on September 13, 1948. He is a professor of drawing and painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Ljubljana and the Faculty of Education, University of Ljubljana. It has a long career as an internationally renowned Slovenian artist.

(It is the opening speech of the solo exhibition of Mexican artist Humberto Ortega Villaseñor at Cankarjev dom in Ljubljana, Slovenia on the evening of June 12th, 2013):

H. O. Villaseñor and his light

The paintings of H. O. Villaseñor in a sense present the body/give one’s body, drawing one introspectively into a gaze that all beings share in the form of anxiety or aloneness. They present us with the very source of the artist’s movement, his layering of colour as a kind of primeval flotsam that drifts into us through a magic, archaic eye, bringing the sensations of our own bodies into equilibrium. This superstructure of pigmented surfaces, these painted bodies, framed by the symbolic sketch of a painting, emerge in the space of possibilities, demanding their own existence as unconsciously reshaped attachments to our bodies (the world). They are like emotional balance endowing our consciousness, and through their traditional Mexican heritage they convey their own as well as our light.

We are talking about a pigmentary structure here that is magically whole, dreamt through as if a body within a body, as if gazing into light in its totality – or like some ancient photic chaos that disturbs our very being, an aspect ive physical trace that is at once our body and a trace of the perennial cycle oflife and death.

This reborn primevalness with its archaic disposition of pigment and light; the magic language of signs and their sublime fluidity – this is the body of the artist himself. In our positions of vulnerability, with social media technologies proliferating and perpetuating all kinds of manipulations, the works of this Mexican artist and thinker constitute a self-critical direction rooted in the Mesoamerican cultural heritage.

Contemporary painting practices are ever more variable, impermanent and fragmented. The structure of the painting has expanded, in one instance presenting itself as a palm-sized book, in another as an object, a painting and part of a broader open or closed space, landing on a pedestal as a found or chosen object with some conceptual intervention. In the works of Villaseñor this process is idealized and subject to spontaneous utterances. This is because its concern is with spiritual vision that doesn’t need spatial support, but rather manifests itself in a traditional form as a link binding us to the past with which it seamlessly connects its own being. His work is a meditation on light in which the artist subjects his perspective to spiritual seeing. We are talking about a non-mimetic space here, a space that encompasses the gesture (brush stroke?) and the fluidity or condensation of colour alongside expressive archaic accents. The substance of’ his space is the speech of light that generates ongoing creative unrest.

Materiality as accentuated corporality of Villaseñor’s works, as these are encrusted onto the light of the gallery walls, is a mode of aesthetic contemplation that sustains itself through the image of all images, the all-present structure of consciousness constituting our self-reflexive powerlessness and redemption. Alongside aesthetic contemplation, Villaseñor’s pictorial language attracts us like a chink promising to reveal what is recognizable and what is not – what ís visible and invisible in our human reality.

Villaseñor’s vision of the world embodies the power of form. Out of the empty spaces, a sense of belonging and networks of meanings akin to a cultural chain are forged. Neither actively seeking the world nor anxiously withdrawing from it, the artist’s work comes rather as a vital recognition of the love of artistic creation and belonging to life.

Zdenko Huzjan,

Ljubljana, Slovenia

June 2013

Light

The white light coming from the sun is the original source of color. What we define as color is just a conventional term applied to an object or, form perceived as a reflection (1). The color e see is thus only a fraction of light reflected from the object in question.

Me exit to light contains the exit to space. The man who feels having gained in space feels also to have come out to light. However. , fear is the reason behind our search for something without resistance to light. For a god of vision, of intelligence. For a knowledge shedding light on the inner space where human vision originates, blind man who sees through our eyes (2).

Work

It is difficult to circumscribe with words the ideas and feelings emanating from H.O. Villaseñor’s pictoric universe, being as it is grounded on pre-Columbian symbolism. Villaseñor paints as if he were approaching reality, the one that, in the words of Mircea Elíade is free from the automatisms of profane progress. The attempt is ambitious enough, for we discover a .set of actions evocative of a spiritual ceremony trying to aprehend and digest at the lame time coda and vestiges of the pre-Columbian world. Inside this undercurrent, one can perceive a purpose to recreate the misterious assembly constituted by signs. A labour of hints and cracks reshaping a language whose ultimate evolution, according to Laurette Sejourné was confiscated in the Xth century by the warrior forces heir to the mythical space of middle-America.

The decadence of cultures has always had the same cause: the dogma-clad drift towards eliminating symbolic depth from the mythical image, turning it into a simple reality (3). Thus the importance of finding the grooves marked by pre-Aztec cultures, in a drive to gather the precious seeds of religious thought left behind their more evolved forms. Texture, obviously, does not attempt to rescue ornamental or stylistic archetvpes: nor rekindle a mixture of them. In active expression we are not allowed to identify traces of a cultural-specific order, or seek out references of a regional nature. The work is not meant to celebrate the details of a given nationalistic school, or preserve certain attributes of mexican folklore. lt is impossible, in this sense, to rationalize Villaseñor’s work: being inherent to emotion, it is immaterial to reason.

“The organization of Villaseñor’s private paper cosmos resembles a sacred territory, with a special respect for natural symetry and mandalic structuring. His resurrected creatures inhabit this space: they are the ancestral toltec symbols”

Raúl Aceves, “La Señal Futura”, in Paréntesis, (Año 1 Num. 10), México, 1988.

A remark is here in order: Villaseñor’s animals are not awarded an animistic quality. He uses above all their ancestral representation impact to strengthen values greater than their visual component. Values constituting symbols harmonically arranged “as if they replicated the order of the universe “, as Beatriz de la Fuente might say (4). We are not dealing with totemic sparkings, but with images whose unicity reproduces in a way the primary structures of everything. In this sense, the symbol bequeaths its message and fulfills its function even when meaning eludes us (5).

“Villaseñor is a contributor to the enormous task of awakening the essential Mexico, trascending the institutional Mexico. In this time when the sleepers believe themselves awake, Villaseñor sounds like an alarm clock in our very tympani. With the music of color and the architecture of forms, he builds us a cave, a nest, a pond where a sun and a cricket may live, and if we touched them, they could just jump off or burn our finger”.

Raúl Aceres, op.cit., p.24.

Perception

H.O. Villaseñor believes it is time to fall back. Painting cannot ignore the omens of change in the air, towards a new cultural era in Mexico. The fine arts need not continue in their traditional role as portrayors of an esthetic code that long ago extinguished its best messages. In his view, the limits to hereness can be trascended, possibly by just ignoring the lamentations of a certain decadent vanguardism and the empty of meaning death throes of industrial modernism. This does not necessarily means a closing in the generic meaning of the term, but only the acknowledgment o f those vanishing pulsations of the many pictoric schools from the traditional metropolis. As different thinkers have stated already, “…art runs in fascination towards dissonances without solution, towards opposites showing, on the one hand, their irreductibility and, on the other, their denial (6).

Notwithstanding Mexico’s immersion in the sorrows of the present -which could well be cause of its recent cultural lackluster- important underground currents are still intact. In the author’s vision, his own evolving vocation as a person is already formed. His quest constitutes a commitment to a particularist universalism and with a creative instant prior to the need of submitting its aesthetic condition as vehicle for messages beyond themselves. Life, in this sense, is not made of moments, but these moments are consumers of a plot that needs to be interpreted Because of this, any art not including such a symbolic overtone has only a relative value from the historical viewpoint, valid only for a dated period but inocuos from the viewpoint of its mythical repercussion.

Notes

1. Apud, Hayten, Peter J. El Color en las Artes, (IEDA, Barcelona), c1958, 1962, pp.17-18.

2. Zambrano Maria, El Hombre y lo Divino, (FCE, México), c1955, 1986, p.129.

3. Diel, Paul, Dios y la Divinidad, (FCE, México), cl986, pp. 32-33.

4. Apud. Los Hombres de Piedra, (UNAM, México), c1977, 1984, p.93.

5. Eliade Mircea, in Sejourné Laurette, Foreword to El Universo de Quetzalcóatl, (FCE, México), c1962, 1984, p. 185.

6. Zambrano, María, op.cit, p.185.

Sources of Inspiration*

(H.O. Villaseñor)

Symbols have a sacred meaning. They are like signs of a higher language that analysts say cannot be translated into rational terms. When producing a painting, I never restrict myself. I try to keep my-symbol receiving mechanism as open as possible, so that the messages flow without interference.

That is why I’ve never paid much attention to the myths and legends that link these Pre-Columbian symbols to our times. My approaches to archetypes are neither exhaustive nor systematic. They don’t try to be. They are more the result of coincidence, or at most, of a process of contemplation and reflection on forms and relations. I don’t nose around in books either. I’m not interested in accumulating erudite learning. I visit sites, I consult codices, I observe illustrations in books containing drawings or photos of ceramics, glyphs or ceremonial centers. I try not to read or immerse myself in texts more than is necessary. I distrust interpretations that tie together too many threads and then turn out to be very poor, overly descriptive, or top heavy with academic prejudices. In other words, I avoid influences based on external appreciation.

I must admit, however, that there is a body of ideas and beliefs that nourish my thought. I identify with thinkers that espouse more open-minded criteria for focusing on the past. They are the ones who have encouraged me to walk down this intuitive road where, as far as possible, the rigoristic predicaments do not prevail. I try to understand the sacred language, paradoxical as it may seem, in a direct and objective way.

This school of writers—more than scholars, they seem to be warp weavers—proposes an integrating reinterpretation of the traces and vestiges of ancient Mesoamerican man and civilization, on the basis of its symbolic weight: León Portilla, Sejourné, Elíade, Jung, Leví-Strauss, Paz, Bonifaz Nuño, Artaud, Argüelles and others. Thinkers who summon us to a new vision of the past on the basis of direct contact with the legacy itself.

Obviously there is a substrate that is the common denominator of the paintings. The presence of essential elements from the animal, vegetable and mineral kingdoms. The interplay of essences such as fire, air, earth and water; sky, earth and stars; tree, serpent, eagle, etc. Different objects that, while projecting a vision very specific to the Mesoamerican world, also have a decisive symbolic content of a collective nature. Finally, the conscious use of two-dimensionality, bipolarity, symmetry, numbers and light as chromatic axes or cosmogonic reference points.

Creative process

Usually when I come in contact with a frieze, a bas-relief or a small drawing, I discover features—perhaps insignificant at first glance—that seem to call out to me and invite me to meditate on what they might mean. Later, I get my nerve up to make a sketch, trying to reflect the relationships between color and form that seem important to me.

After that comes the transfer to bark paper or canvas and the color tests. The results are always unpredictable.

Nevertheless, since the works remain close to me for a long time, they continue ripening until the moment when their intensity tells me that content is expressed down to the last meaning. In other words, I can tell when the painting is precocious and the message is still trapped inside, and when it has been expressed. As if it were an enigma in which space (the surface) and time (of the creative atmosphere) join hands. Generally I’m not drawn to all-encompassing expressions. Sometimes I perceive a small line and its relationship with another body. It might be an arrowhead, or a small feature of some composition. Contemplation and meditation are essential parts of the further development of each work.

Sometimes the process happens by itself. I feel the need to sketch some animal or some plant because of the power they have inside. That’s why it’s not uncommon to discover later that the archetypal foundation of many of my paintings already existed in some structural detail or on a tiny fragment of pottery. From there I moved to the conceptual level, for example, with my use of symmetry and two-headed anthropomorphic figures (which I cultivated for a long time in the paintings dating from 1984 on). A tendency that matches certain conclusions that the poet Bonifaz Nuño would espouse in 1987, about the abstract representations of the god Tláloc.

In the next section I reconstruct the processes I followed when putting together some of my works. My intention is not only to refer to the diversity and extent of their links with Pre-Columbian records, beliefs and myths, but also to the peculiar details that occurred at the time of their gestation. Obviously, the sum of all the experiences that I had in each case is immense, and very intimate, and would require an analytical effort much greater than the one I am attempting here. However, it is fortunate that almost all the works share an analogous perceptive criterion that consists of capturing and re-creating, in a modest way, part of the Pre-Columbian consciousness that is reawakening in the next cultural stage that I am convinced is coming.

Royal Ducks

(Prototype of linkage with a representative fragment)

In this case, the eye almost automatically detects the upper detail of a banner held by the representation of Tláloc in Tepantitla, Teotihuacan. It suspects that it is a detail with wonderful symbolic value. The eye leads the perception toward a meditative exercise. The lines of the detail and the relationship among them in space bring to mind an almost elliptical solar plexus containing a beating heart in red, which instead of illuminating within the vibration of this tonality, tends toward the annular pinks both inside and outside of the plexus.

The three forms that emerge from this element must be ducks. Animals that, given their size and lineage, cannot be common, but royal ducks. The kind that live near Veracruz and that have a magical hierarchy. The mind now remembers the body of the San Lorenzo duck (The Stone Men, Beatriz de la Fuente, UNAM, Mexico City, 1984, illustrations # 17 and 17a), whose abstraction becomes square, as well as certain representations of the duck among the Huastecans of the past and present.

Underneath the three figures, unity converges. The three-headed animal stands atop a throne that implies the devotion contained in the two heavenly bodies (like a guiding star and the next one down). The misty surroundings signify at the same time the beginning and end of time. The separate value of the elements gives way to the representative value of the nucleus (a heart that beats within the trinitarian unity). Mystical love is refracted with a force and sweetness that allow the composition to move on the material plane, only to culminate in a full-scale vision pointing perpetually to the heavens.

Lobster

(Prototype of linkage with a detail from a clay figurine)

In this case, the eye almost automatically detects the upper detail of a banner held by the representation of Tláloc in Tepantitla, Teotihuacan. It suspects that it is a detail with wonderful symbolic value. The eye leads the perception toward a meditative exercise. The lines of the detail and the relationship among them in space bring to mind an almost elliptical solar plexus containing a beating heart in red, which instead of illuminating within the vibration of this tonality, tends toward the annular pinks both inside and outside of the plexus.

The three forms that emerge from this element must be ducks. Animals that, given their size and lineage, cannot be common, but royal ducks. The kind that live near Veracruz and that have a magical hierarchy. The mind now remembers the body of the San Lorenzo duck (The Stone Men, Beatriz de la Fuente, UNAM, Mexico City, 1984, illustrations # 17 and 17a), whose abstraction becomes square, as well as certain representations of the duck among the Huastecans of the past and present.

Underneath the three figures, unity converges. The three-headed animal stands atop a throne that implies the devotion contained in the two heavenly bodies (like a guiding star and the next one down). The misty surroundings signify at the same time the beginning and end of time. The separate value of the elements gives way to the representative value of the nucleus (a heart that beats within the trinitarian unity). Mystical love is refracted with a force and sweetness that allow the composition to move on the material plane, only to culminate in a full-scale vision pointing perpetually to the heavens.

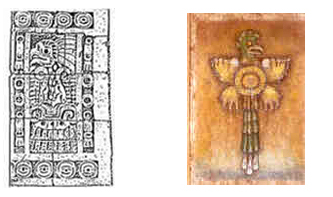

Royal quetzal shield

(Prototype of linkage to a plurality of signs)

The elements that make up this work come from different records. It was necessary to spend a long time contemplating the bas-reliefs on the columns of the Butterfly Palace in Teotihuacan. The hybrid’s head seemed to be fed with the nectar carried by thousands of bees. However, when deciding on its configuration, I felt the need to equip this specimen with wings as delicate and claws as powerful as those of a butterfly-tiger, that lifts itself into the sky after seizing hold of the earth.

[Perhaps the combination of these elements came from the memory of a small bas-relief on a bowl found in Santiago Ahuizotla, (cfr. Winning, Von Hasso, Introducción a la iconografía de Teotihuacan, UNAM, t.II, p.22, illustr. 7a)].

On the quetzal’s breast a stylized sunflower can be seen, and from the lower petals the feathers of the tail emerge. The feathers are transformed into rain, probably evoking the scroll figures that appear in many manifestations of rain in the polished ceramics of Zacoala and Atelelco (ibid., 10.13, illustr. 6a and 10f).

With this creation I tried to achieve an integrating and emblematic vision of rain as the manifestation of the purifying power that comes from the higher regions.

Post scriptum

I would like to point out that I paint what I paint freely (it comes to me, it occurs to me, I feel it), although later I am surprised to discover that what I have put down may correspond to an order that others have studied systematically. Never the other way around.

I would also like to point out that the brief analysis that I have made implied an enormous effort of memory; an organizational challenge and the painful need to clarify some of the references that colors and associations, i.e., images, evoked in me. Unfortunately this examination has forced me to explain on a rational level something that germinates and ripens in the intuitive realm. In this sense, it must be said, the task that I have been asked to carry out, has been a thankless one, to the extent that I am not in the position to disentangle something as unique and elusive process as the creative process. I am convinced that it is impossible to dissect each part without doing violence to the whole in some way. Works of art are made, and enough said. Others will have the task of discerning their perspective and limits, their origin and profile.

I must insist that my role as a painter is very modest and different. To say otherwise would be like denying the hands I was given and the world I was born into. I am, in short, a painter of these times, among many others.

* This analysis, along with the biographical summary that appears at the following section, form part of several introspective works that the Ram Scale art group in New York requested of the author. They were written up in 1990 and 1991 respectively. They represent the informational source of the material that was planned to be published in advance of the individual exhibition that this group put together in New York in 1994.